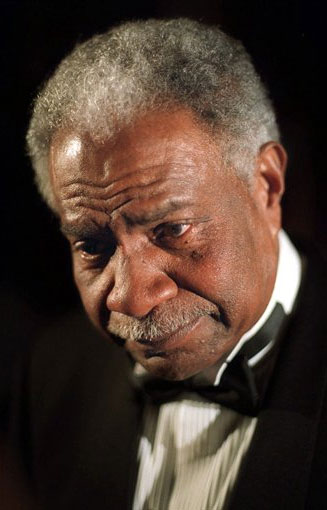

Ossie Davis, whose rich baritone and elegant, unshakable bearing made him a giant of the stage, screen and the civil rights movement often in tandem with his wife, Ruby Dee has died. He was 87.

Davis was found dead Friday in his hotel room in Miami Beach, Fla., according to officials there. He was making a film, “Retirement,” said Arminda Thomas, who works in his New Rochelle office and confirmed the death.

Miami Beach police spokesman Bobby Hernandez said Davis’ grandson called shortly before 7 a.m. when Davis would not open the door to his room at the Shore Club Hotel. Davis was found dead, apparently of natural causes, Hernandez said.

Davis wrote, acted, directed and produced for the theater and Hollywood. Even light fare such as the comedy “Grumpy Old Men” with Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau was somehow enriched by his strong, but gentle presence. Davis and Dee celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 1998 with the publication of a dual autobiography, “With Ossie & Ruby: In This Life Together.”

Their partnership rivaled the achievements of other celebrated performing couples, such as Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy. Davis and Dee first appeared together in the plays “Jeb,” in 1946, and “Anna Lucasta,” in 1946-47. Davis’ first film, “No Way Out” in 1950, was Dee’s fifth.

Both had key roles in the TV series “Roots: The Next Generation” (1978), “Martin Luther King: The Dream and the Drum” (1986) and “The Stand” (1994). Davis appeared in several Spike Lee films, including “Do the Right Thing” and “Jungle Fever,” in which Dee also appeared.

Davis had a guest role as the father of two women characters in Showtime’s dramatic series, “The L Word.” He appeared in one episode in the first season, then returned for three episodes for the season about to begin, where his character takes ill and dies.

“We knew that we were working with a powerful, important actor,” executive producer Ilene Chaiken said Friday. “Ruby Dee sat with me and watched as he filmed his death scene. It was extraordinary.”

Among Davis’ more notable Broadway appearances was his portrayal of the title character in “Purlie Victorious” (1961), a comedy he wrote lampooning racial stereotypes. In it, he played a conniving preacher who sets out to buy a church in rural Georgia. In 1970, Davis co-wrote the book for “Purlie,” a musical version of the play. A revival of the musical is planned for Broadway next season.

Actors’ Equity Association issued a statement Friday calling Davis “an icon in the American theater” and he and Dee “American treasures.” House lights for Broadway marquees were to be dimmed Friday at curtain time.

In 2004, Davis and Dee were among the artists selected to receive the Kennedy Center Honors.

“His greatness as a human being went far beyond his excellence as an actor,” former New York Governor Mario Cuomo said Friday. “Ossie was a citizen of the country, first, and the world. He and his wife were activists and they took it seriously.”

Dee was in New Zealand making a movie at the time of Davis’ death, said his agent, Michael Livingston.

When not on stage or on camera, Davis and Dee were deeply involved in civil rights issues and efforts to promote the cause of blacks in the entertainment industry. In 1963, Davis participated in the landmark March on Washington. Two years later, he delivered a memorable eulogy for his slain friend, Malcolm X, whom Davis praised as “our own black shining prince” and “our living, black manhood!”

“In honoring him, we honor the best in ourselves,” said Davis, who reprised his eulogy in a voice-over for the 1992 Spike Lee film, “Malcolm X.”

Davis directed several films, most notably “Cotton Comes to Harlem” (1970). Other films include “The Cardinal” (1963), “The Client” (1994) and “I’m Not Rappaport” (1996), a reprise of his stage role 10 years earlier.

On TV, he appeared in “The Emperor Jones” (1955), “Miss Evers’ Boys” (1997) and “Twelve Angry Men” (1997). He was a cast member on “The Defenders” from 1963-65, and “Evening Shade” from 1990-94, among other shows.

Davis had just started his new movie on Monday, Livingston said. “Retirement,” a comedy about an elderly group of friends, also starred Jack Warden, Peter Falk and George Segal.

The oldest of five children, Davis was born in tiny Cogdell, Ga., in 1917, and grew up in nearby Waycross and Valdosta. He left home in 1935, hitchhiking to Washington, D.C., to enter Howard University, where he studied drama, intending to be a playwright.

His career as an actor began in 1939 with the Rose McClendon Players in Harlem. After the outbreak of World War II, Davis spent nearly four years in service, mainly as a surgical technician in an Army hospital in Liberia, serving both wounded troops and local inhabitants.

Back in New York in 1946, he debuted on Broadway in “Jeb,” a play about a returning soldier. His co-star was Dee. In December 1948, on a day off from rehearsals from another play, they took a bus to New Jersey to get married.

As black performers, they found themselves caught up in the social unrest of the then-new Cold War. In one instance, Davis stood by singer Paul Robeson even as others denounced him for his openly communist sympathies. “We young ones in the theater, trying to fathom even as we followed, were pulled this way and that by the swirling currents of these new dimensions of the Struggle,” Davis wrote.

“Look up the word ‘activist.’ Think about what it means to be a role model,” Bill Cosby said of Davis in a statement Friday.

Besides Dee, Davis is survived by three children Nora, Hasna and Guy, a blues artist, and seven grandchildren.